Imperialist feminism redux

The occasion of International Women’s Day is an apt time to discuss how abstract ideas of global sisterhood and women’s universal human rights hide the actual differences of class and social location which divide women in the real world, and how certain varieties of feminism not only cannot address the real foundations of women’s subjugation, but may in fact contribute to them.

In the 19th and early 20th century, the civilising mission through which colonialism was justified was supported by western feminists who spoke in the name of a ‘global sisterhood of women’ and aimed to ‘save’ their brown sisters from the shackles of tradition and barbarity. Today, this imperialist feminism has re-emerged in a new form, but its function remains much the same – to justify war and occupation in the name of ‘women’s rights’ . Unlike before, this imperialist feminist project includes feminists from the ‘Global South’.

Take, for example, the case of American feminists, Afghan women and the global war on terror (GWoT).

Ever since 9/11, there has been a constant effort to build a broad consensus around the need for a sustained US military presence in Afghanistan. In the early days of the war, the idea of retaliation and revenge for the attacks on the World Trade Centre had an obvious appeal for a wide range of the political spectrum. The argument about protecting ‘our way of life’ from a global network of Islamic extremists proved persuasive as well. All through this period, there was one claim that proved instrumental in securing the consent of the liberals (and, to some extent, of the Left) in the US – the need to rescue Afghan women from the Taliban. This justification for the attack on Afghanistan seemed to have been relegated to the dustbin of history in the years of occupation that followed, reviled for what it was, a shameless attempt to use Afghan women as pawns in a new Great Game.

As the United States draws down its troops in Afghanistan, however, we have begun to see this ‘imperialist feminism’ emerge once again from a variety of constituencies both within the United States and internationally. One such constituency locates itself on the left-liberal spectrum in the United States and consists of an alliance between self-de fined left-wing feminists in the United States and feminists from the Global South (specifically Muslim countries such as Algeria and Pakistan).

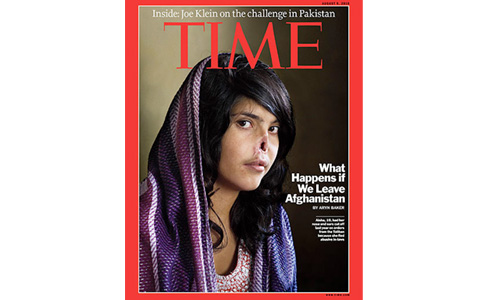

The past 11 years of war and occupation in the name of women’s rights should have served as a cautionary tale for how easily liberal (and left-liberal) guilt can be used to authorise terrible deeds. Especially in view of the clear evidence showing that the status of Afghan women has seriously declined during this time, and in the face of consistent critiques of the occupation by Afghan (women) activists such as Malalai Joya. Instead, the idea that the US/Nato war in Afghanistan has been good for Afghan women continues to hold sway within the liberal mainstream in the United States. In August 2009, for example, Time magazine’s cover featured a dis figured young Afghan woman with the caption, ‘What Happens When We Leave Afghanistan’.

More recently, in May this year, Amnesty-USA ran a campaign openly supportive of the US/Nato presence in Afghanistan just in time for the Nato summit in Chicago. Ads on city bus stops featured images of Afghan women in burqas along with the caption: Human Rights for Women in Afghanistan. Nato: Keep the Progress Going! Alongside this ad campaign, Amnesty conducted a ‘shadow’ summit featuring former secretary of state Madeline Albright, with promotional material rehashing Bush-era ‘feminist’ justifications for the war in Afghanistan and claiming that the 11 years of war and occupation had improved conditions for Afghan women.

The fact that the meme of the Muslim woman who must be saved from Islam and Muslim men – through the intervention of a benevolent western state – 11 years after the very real plight of Afghan women was cynically deployed to legitimise a global war, and long after the opportunism of this imperialist feminism was decisively exposed, points to a serious and deep investment in the assumptions that animate these claims. These assumptions come out of a palpable dis-ease with Islam within the liberal mainstream and portions of the Left, a result of the long exposure to Orientalist and Islamophobic discourses.

Within this liberal discourse, secularism is posited as the necessary prerequisite for achieving equal rights for women. Crucially, democracy is often seen as a problem for securing such liberal rights within the Arab/Muslim world. The less-than-enthusiastic support for the Arab Spring by liberals on the basis of a fear that the Muslim Brotherhood would come to power (thereby implying that the human rights/women’s rights record of the regimes they were replacing was somehow better) illustrates the liberal anxiety regarding democracy when it comes to the Arab/Muslim ‘world’ and hints at the historical relationship between women’s movements and authoritarian regimes in the postcolonial period.

Despite the existence of a very real gendered racial project at the heart of the war on terror, and the mainstream acceptance of the violence that it enables on Muslim men in particular and Muslim families/communities in general (since Muslim men do not exist in a vacuum), a new front of international feminists and human rights advocates has emerged to challenge what they see as the international human rights community’s inordinate focus on Muslim men as victims. This focus, they argue, constitutes a betrayal of Muslim women – and of human rights advocates in Muslim communities and countries fighting against Islamic fundamentalism – because it occludes the role of Muslim men (all Muslim men, not specific ones) as perpetrators of violence against (all) Muslim women. And so, in the case of Anwar al-Awlaki, the efforts of the Centre for Constitutional Rights to uphold the constitutional rights of American citizens (leave alone lesser humans) to a fair trial were actually reviled.

Even as the United States officially begins to wind down its war in Afghanistan, the GWoT – recently rebranded as the Overseas Contingency Operation by President Obama – is spreading and intensifying across the ‘Muslim world’, and we can expect to hear further calls for the United States and its allies to save Muslim women. At the same time, we are seeing the mainstreaming and institutionalisation of a gendered anti-Muslim racism within the west, which means that we can also expect to see more of the discourse which pits the rights of Muslim men against those of Muslim women.

All this is not to deny the very real violence and oppression faced by Muslim women, or to deny the Taliban’s violent gender politics. However, it is to caution against seeing Muslim women as exceptional victims (of their culture/religion/men), and to point out both that there are family resemblances between the violence suffered by women across the world and that there is no singular ‘Muslim woman’s experience’. It is to note, as Malalai Joya keeps reminding us, that violence against women in Afghanistan is not the purview of religious forces such as the Taliban; the warlords of the Northern Alliance and the American occupation are also perpetrators. And then there is the structural violence of poverty, which is exacerbated by the long years of war and occupation.

International Women’s Day was established by people who understood women’s rights to be part of the struggle against capitalism and imperialism. Perhaps it’s hardly surprising that the origins of March 8 have been forgotten in this age of a depoliticised discourse and practice of ‘human rights’. If we are indeed committed to improving women’s lot, we must realise that these twin evils continue to lie at the heart of the problems faced by the vast majority of women across the world, and especially in ‘Muslim’ countries such as ours.

A longer version of this article appeared in Dialectical Anthropology (Volume 36, Issue 3-4) and can be accessed here.

Author Sadia Toor is Associate Professor of Sociology at the City University of New York. Her book, State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan was released in 2011 by Pluto Press.

Comments